Much Obliged: Going Beyond ‘Thank you’ with ESL Students

Would your answer be:

The correct answer is D, naturally. The very notion that one country can be ‘better’ than another is childish, tantamount to inviting wrong-headed nationalism, and, in any case, impossible to quantify or support. What on earth would make France ‘better than’ Australia? Or China ‘better than’ Vietnam? You might have your own criteria – living standards, national achievements in science, the arts or sports, or other factors – but humanity as a whole would find it quite impossible to agree on a ranking of its members. What of tiny Bhutan, for example, whose government eschews headlong development in favor of measuring the ‘Gross Domestic Happiness’?

Still, it is a popular notion that countries can be ranked from best to worst, and it’s very common for language to play a guiding role. I’m going to bet that, if your answer wasn’t ‘D’, it was probably ‘A’, unless you’re a Brit or an American. (I’m both, by the way, but I still answered ‘D’, because I’m a sane and reasonable person). When ‘ranking’ countries, would you be tempted to place at the top the countries with the same first language as your own?

Very generally and simplistically, and for a host of reasons, we tend to regard our own language, culture (and often political systems) as the best on Earth. In the case of native English speakers, this is an opinion which seems to be born out by the evidence. After all, the British conquered much of the world during the time of the Empire, and the US and Commonwealth nations have an enviable record of development and achievement. The first words spoken on the Moon were in English. Many of the world’s most respected and treasured novels are in English, as are the vast majority of the most popular movies and a large chunk of the best-known music.

By referring to English as ‘the language of Shakespeare’, and by labeling the most formal, educated version of it ‘The Queen’s English’, we as English speakers dine out on the celebrity of the language’s most respected figures. We might note that virtually every other modern language now features words imported from English (from ‘le weekend’ in French to the endlessly wonderful Wasei-Eigo transliterations in Japanese), and that as technologies and societies change, it is English which is first to coin new expressions. It seems supple and adaptable, the hallmarks of a language which deserves its current primacy in world affairs.

But be careful. If we look back at the history of the British Empire, for example, a tiny handful of alterations to the sequence of political and economic chess moves which defined that era would have brought mightily different consequences. What if, for example, the Spanish or Portuguese empires had conquered all of North America, South Africa and India? Alternatively, what if China’s imperial ambitions had been fully realized (as detailed in Gavin Menzies’ largely discredited, but nonetheless fascinating book, 1421)? Would Spanish now be the accepted lingua franca, with one variety elevated to ‘Received Pronunciation’, a sign to the world of one’s education and culture? Or, would we all be encouraged to study and enjoy ‘the language of Confucius’?

Such outcomes are little more than a historical coin toss. Although I love the English language, I’m more than happy to concede that it is flawed – not least in the absence of a phonetic approach to spelling – and that learning it well is a major challenge. It’s full of homophone pairs, there is a dizzying spectrum of nuance to its vocabulary, and it’s spoken very differently from place to place. But there’s something else which prevents me from lauding my own language and culture as the best: I know just how much I don’t know.

Congratulations if you’re an exception, but most native English speakers cannot claim fluency in a second language. I believe that this worrisome phenomenon is contributing to a sense that English richly deserves its position as the one true international language. If we’ve never experienced other languages, and are unfamiliar with their power, craft and subtlety, we assume that English has no true competitor for its crown.

Any assertion that English is the ‘best’ language is simply untrue, and cannot be supported.

Any assertion that English is the ‘best’ language is simply untrue, and cannot be supported. Such a claim would require that one had native-level fluency in every one of the five thousand languages spoken on Earth, and even then it would still be a dumb thing to say. We all use languages differently, and they all change constantly. If we assert the primacy of modern English, do we also claim that Middle English, the language of Bede and Chaucer, was superior to its cousins? I encourage you to set this idea aside, and instead embrace a very different view.

The languages spoken by our students are just as rich and nuanced as our own, and they love the places they come from just as genuinely as we do. The only measure of a country, if there can even be a meaningful one, is how open it can make itself to ideas and languages from elsewhere. Understanding these fundamental truths revitalized my teaching, and in a larger sense, my worldview. During that same period, some twenty years ago now, I also read Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel. If you ever find yourself wondering why some nations are rich, and some poor, and how English gained its global primacy, please read it; I hope you find it as enlightening as I did.

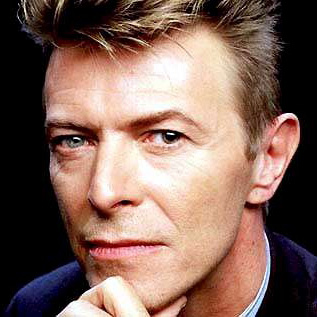

William Shakespeare, the Queen, and the leading musicians, novelists and poets of the English language are great ambassadors, but once we move away from the ‘greatest hits’, we’re quickly among the less enviable, and indeed the downright shameful. I’m delighted that English-speaking musicians include among their number Henry Purcell, Ralph Vaughn-Williams, John Lennon, Elvis Presley, and the late, great David Bowie. But they also include purveyors of artifice, the greedy, the talentless and the intellectually bankrupt. I need not name names, because you know just who I mean.

I love it too, but I wouldn’t want the Internet held up as a beacon of the transcending, unifying powers of English.

And if you’re tempted to laud the Internet as a model of how English has spread openness, education and freedom throughout the connected world, then I’d agree, before reminding you that it’s also brought unfettered pornography, hatred, violence, gambling, and literally countless ways to waste our time. I love it too, but I wouldn’t want the Internet held up as a beacon of the transcending, unifying powers of English.

Another of our greatest exports has been the bi-cameral parliamentary system of democracy. No less a man than Winston Churchill described it as ‘the worst form of government, except for all the others’. Through this political lens, we’ve been invited to view absolute monarchies and dictatorships as unforgivable thefts of their public’s freedoms.

But again, be careful. Local solutions work best, and there can be no one-size-fits-all answer to the world’s problems. Neither a single political system, approach to art, philosophy of education, or indeed language can claim to be ideal in every context it’s been tried. A Congress, Parliament or Duma might seem best to you, but it would be a brave and naïve political commentator who claimed they work flawlessly, or even, sometimes, at all.

I don’t know about you, but I’d rather be accused of relativism than of harboring imperial ambitions.

Besides, such systems can’t hope to be sufficiently responsive to every possible historical, cultural and political environment. This might sound like hollow cultural relativism, through which we turn a blind eye to human rights abuses because they’re also part of the local solution. I don’t know about you, but I’d rather be accused of relativism than of harboring imperial ambitions. I may not agree with how other countries run their affairs, but I uphold their right of self-determination.

Consider also that there are many subtleties which English cannot express, and many cultures from which western democracy could usefully borrow. Language and politics are, and should be, a two-way street.

I’m not sure that this discussion yields any ‘teaching tips’ as such, but it’s very worthwhile to assess your attitude to the language and culture you were born in. Consider whether you’re giving other cultures a fair shake. Challenge the assumptions we (perhaps inevitably) have about our students – especially, right now, regarding your Arabic, Russian and Chinese speakers – and assess whether you’re unfairly expecting them to be lofty ambassadors for their culture.

In particular, if you work with young students and teenagers, remember that they did not choose their governments, and would almost certainly prefer that their country, religion and language were heard and seen by the world in a different light.

Above all, consider just how fortuitous – indeed, entirely random – is the current primacy of English in world affairs. It need not have been this way, and in dwelling on this, we may imagine some of the ‘what-ifs’ which remained unrealized, and marvel at the unlikelihood of what has actually transpired.

This is the first step to allowing learning to flow not in one, but in both directions.